HOW TO EXTERNALIZE PROBLEMS

- Derek Hagen

- Aug 3, 2023

- 6 min read

❝Once the problem is named in an externalizing way, then you can become an investigative journalist in your own life.❞ -David Denborough

I’m attending a lecture by Rick, talking about putting ourselves out there and getting out of our comfort zones. During the lecture, Rick tells us that he used to be afraid to do public work, meaning he was afraid to publish his work for fear of being judged and people thinking he wasn’t good enough.

This fear was with him until he realized that his fear was there to protect him. He started seeing fear as a little character in his life. He learned to recognize that when the fear showed up, it was a signal - not to stop doing the work that he was doing - but rather that he had important work to do. He learned to thank his fear for trying to help.

Rick personified his fear and, in doing so, separated himself from the fear and learned to communicate with his fear.

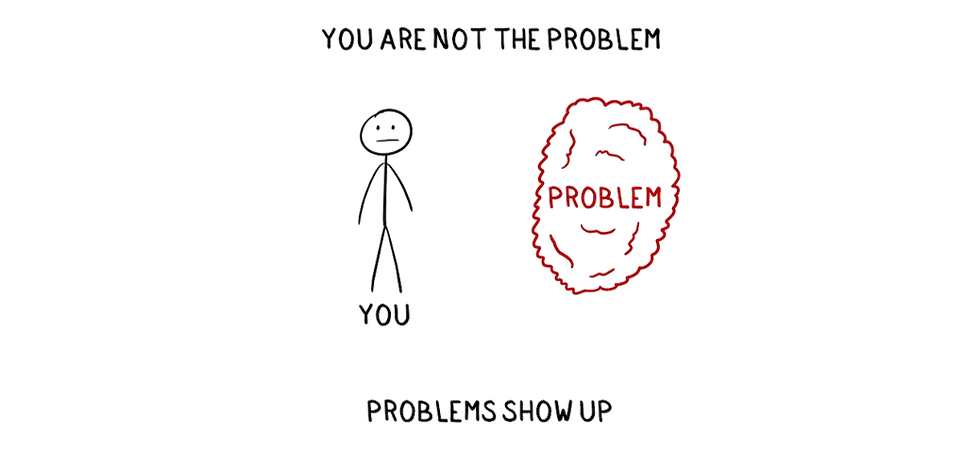

THE PROBLEM IS THE PROBLEM, NOT YOU

When you externalize problems, you start to recognize that the problem is the problem, not you. For example, instead of saying, “I'm a bad person,” you might say, “I'm experiencing some trouble,” or, “Trouble is following me around.”

Externalizing problems gives us the profound realization that since we are not the problem, we can work on solving the problem.

Imagine you sitting there living your life, minding your own business.

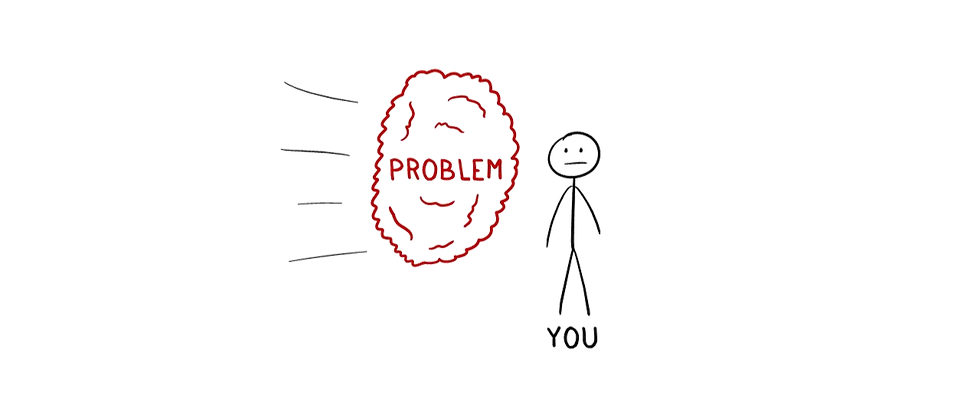

Then, a problem shows up. This could be anxiety, depression, stress, fear, uncertainty, confusion, anger, or any other problem you might encounter.

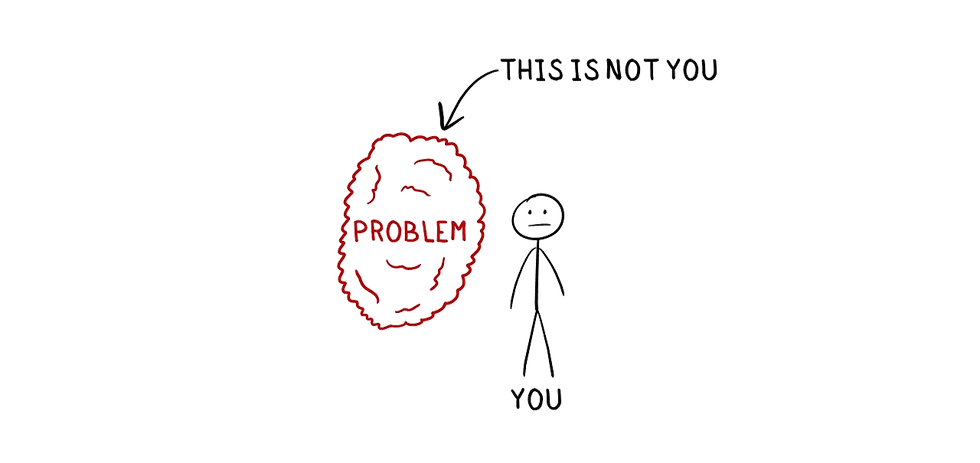

The point is that problems show up. You are not the problem. One helpful way to separate yourself from the problem is to envision it as a separate entity and give it a name.

NAMING THE PROBLEM

To name your problem, you have to separate yourself from the problem and imagine your problem as a visitor. We will always encounter these visitors, and having different names for problems makes it easier to understand what the problem is and what we might do about it.

Imagine you experience some anxiety. Perhaps this anxiety makes it difficult for you to make a decision because, say, you don’t want to make the wrong decision.

Personifying problems involves assigning people-like characteristics to problems as if they are actual characters. Personifying your anxiety might involve imagining what it would look like if it was an actual visitor. Once you know what this visitor might look like, you can give it a name like “The Worrier.”

Then you can view The Worrier as a visitor who shows up when you have a tough decision to make. Instead of saying things like, “I’m worried about making a decision,” you can say, “I must have a tough decision to make because The Worrier is here.”

If you find yourself feeling angry or irritated, instead of saying, “I am mad,” try assigning a name to the visitor. It can be as simple as using the emotion itself as the name. Then, “I am pissed off” becomes, “The Anger is here.”

If it feels like you can never do anything right, you might try naming the visitor The Inner Critic.

Or perhaps you could call your visitor The Judge because you feel as though you’re not quite good enough.

You might even take the personification a step further and assign it a title.

For example, if you constantly find yourself feeling afraid, of anything – the stock market, your boss, your customers, having conversations, anything really – you might call this visitor Mr. Fear.

You can even personify other people’s problems, so instead of telling your child, for example, that they're being bad, you might wonder how long Mr. Mischief has been following them around.

In many ways, this is a very old concept. Many cartoons, when I was growing up, would depict a character feeling ambivalent about a decision - with an angel on one shoulder and a devil on the other. If someone struggling to do the right thing found themselves tempted to cheat, for example, they might say that The Devil came to visit.

It doesn’t always have to be a character. For example, people who feel confused might say that The Fog of Confusion is following them around.

Somebody feeling sad or depressed might say that the cloud of sadness showed up.

Somebody who might make bad decisions for reasons they can’t articulate might say that The Shadow is around.

Naming a problem could be as easy as naming a part of your brain. I have used a metaphor that the brain is like an elephant and a rider, where the elephant represents the subconscious mind that makes about 95% of our daily decisions, and the rider on top represents the conscious, deliberate mind.

The elephant is responsible for survival and is subject to negativity bias. Thus, somebody doing something that seems irrational from the outside looking in could say that their elephant has gained control.

Tim Urban, author of the amazing blog Wait But Why and, more recently, the book What’s Our Problem?, does an amazing job of naming and personifying problems. In his post Why Procrastinators Procrastinate and his very popular TED Talk, Inside the mind of a master procrastinator, he personifies procrastination as the Instant Gratification Monkey. The Instant Gratification Monkey shows up when he has important things to do.

The Instant Gratification Monkey does a great job of distracting Tim, but somehow Tim manages to complete projects on time. This is with the help of another personification that he calls The Panic Monster. The Panic Monster shows up when a deadline is near and is the only one that the Instant Gratification monkey is afraid of.

If you haven’t read the post or seen the TED Talk, I highly recommend it.

You don’t have to come up with a clever name or character if you don’t want to or can’t think of one. You can simply call it “The Problem” or even “It.” The important thing is to view the problem as something that is outside of you.

|

|

The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire measures your level of mindfulness among five interrelated components. These components are observing, describing, acting with awareness, nonjudgment of inner experiences, and not reactivity to inner experiences. They can be helpful in gaining an understanding of the areas of mindfulness in which you may want to focus. |

|

CHANGING YOUR RELATIONSHIP WITH THE PROBLEM

You might be asking why you would go through the trouble of naming and personifying your problems. The real reason is that it helps you change your relationship with problems. First and foremost, it separates you from the problem helping you realize that you are not the problem; the problem is the problem.

Secondly, once the problem has been externalized and named, you can now have a dialogue with the problem. You can ask questions of it and investigate the problem.

Questions you might consider asking The Problem are:

How long have you been in my life?

When are you most likely to visit?

Do you come announced or unannounced, and why?

Are there places, times of the day, or times of the year when you’re more powerful than others?

What effects are you having on me and my family?

These questions offer good insight into why this problem is in your life. Most of these problems were born to protect you. They have your best interest in mind. The only issue is that they often overstay their welcome. They stick around when you no longer need them.

Once you’ve done some investigating, you get to decide whether or not you want to be completely free from this problem or not. You get to decide whether or not you change your relationship with this problem.

THE PROBLEM AND YOUR RESPONSIBILITY

Externalizing problems is a great way to see that there’s nothing wrong with you, but instead, there is a problem in your life. This empowers you to change your relationship with the problem and do something about it if you want to.

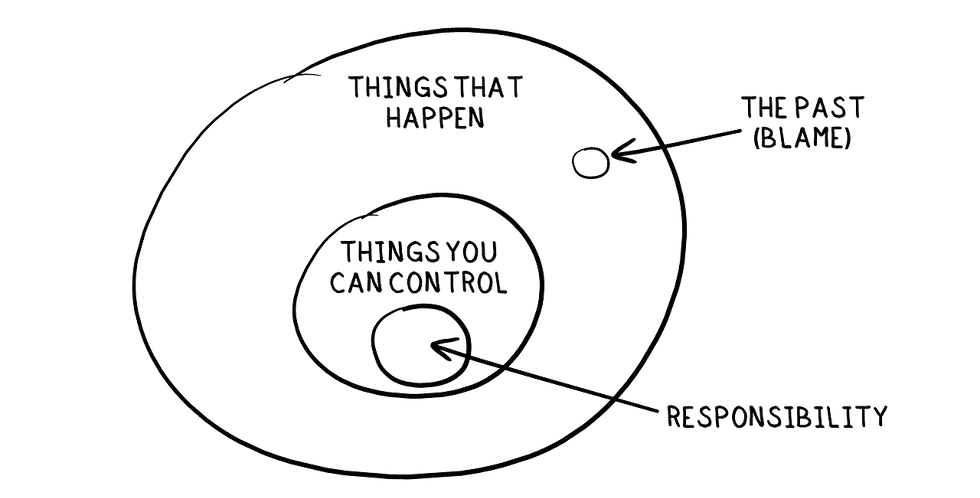

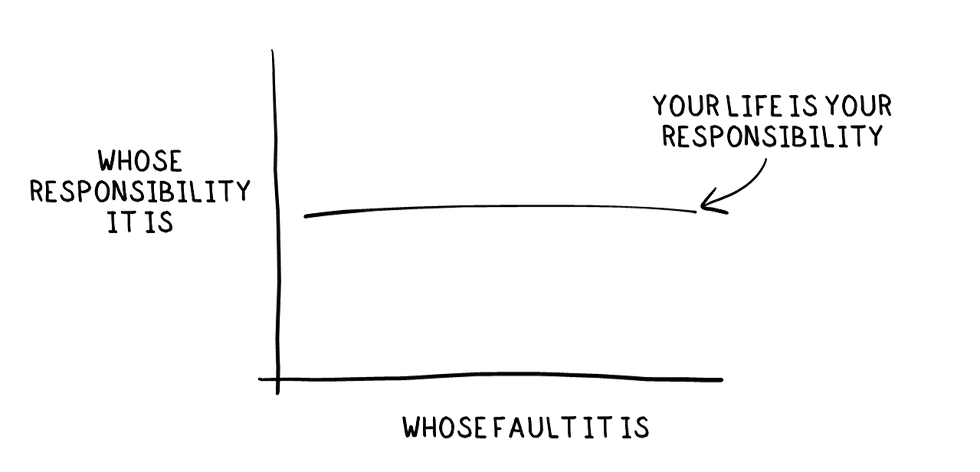

There’s an important caveat, though. Externalizing the problem does not separate you from the responsibility of solving the problem. It can be tempting to fall for something author Mark Manson calls the fault/responsibility fallacy. This is the belief that, because something is not your fault, means you shouldn’t be responsible for changing it. But this is, in fact, a fallacy. Even if something happened that was somebody else's fault, that happened in the past. The past can’t be changed and is out of your control.

On the other hand, you have control over what you do to change or fix the problems that show up in your life. This doesn’t mean you have to do it alone, but it does mean that you are responsible. Your life is your responsibility.

The first step in dealing with our problems is recognizing that we are not our problems. Externalizing problems helps separate us from the problems, empowering us to tackle the problem. A great way to externalize problems is to name the problem. In doing so, you can learn more about the problem's role in your life by investigating it, understanding when it started showing up, and when it is most likely to appear.

You get one life; live intentionally.

Subscribe to Meaningful Money

Thanks for reading. If you found value in this article, consider subscribing. Each week I send out a new post with personal stories and simple drawings. It's free, and there's no spam.

If you know someone else who would benefit from reading this, please share it with them. Spread the word, if you think there's a word to spread.

REFERENCES AND INFLUENCES

Denborough, David: Retelling the Stories of Our Lives Frankl, Viktor: Yes to Life, In Spite of Everything Hagen, Derek: Your Money, Your Values, and Your Life Krueger, David: A New Money Story Manson, Mark: The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck

McAdams, Dan: The Stories We Live By

TED: Inside the mind of a master procrastinator

Wait But Why: Why Procrastinators Procrastinate

Wilson, Timothy: Redirect

Kaiser OTC benefits provide members with discounts on over-the-counter medications, vitamins, and health essentials, promoting better health management and cost-effective wellness solutions.

Obituaries near me help you find recent death notices, providing information about funeral services, memorials, and tributes for loved ones in your area.

is traveluro legit? Many users have had mixed experiences with the platform, so it's important to read reviews and verify deals before booking.