WHAT IS (REAL) RISK?

- Derek Hagen

- Jul 20, 2023

- 7 min read

❝Every man dies, but not every man really lives.❞ -William Wallace in Braveheart

I’m on a bus in Las Vegas on my way to Tropicana. I have to get there by 7 a.m. to catch the shuttle to a small airport to go skydiving. When I get to the hotel, I meet a couple of travelers from other countries, including Juan from Costa Rica. Like me, this is Juan’s first time in Las Vegas and he is also on a solo trip.

Soon, someone comes to us and hands us a stack of waivers to sign. As one might imagine, the waiver is quite long, given that this is for skydiving. I start going through the waiver page by page, scanning all the ways I can be injured or killed doing this activity that I’m paying to do. I have to initial each page as I go through.

Then I look over at my new friend and see Juan flipping through the pages as quickly as possible, scribbling his initials on every page without reading. Jokingly, I ask him if he plans to read anything he has signed.

“No!” he replies. “I really want to skydive, and they don’t let you go unless you sign. I don’t want to know what it says.”

RISK DEFINED

Everybody’s heard of risk. And yet, if I asked you to define it, you might struggle to come up with an answer. Does it mean losing money in the stock market? Does it mean getting fired? What about a car crash?

The answer, as I define it, is the chance that something won’t go away that you want. That can be anything.

Our minds are prediction engines that do a really good job of imagining what might happen in the future. This is true even though we live in a world of probability distributions. It’s not just the case that something either happens or doesn’t. Rather, there are a range of possible outcomes that we can experience.

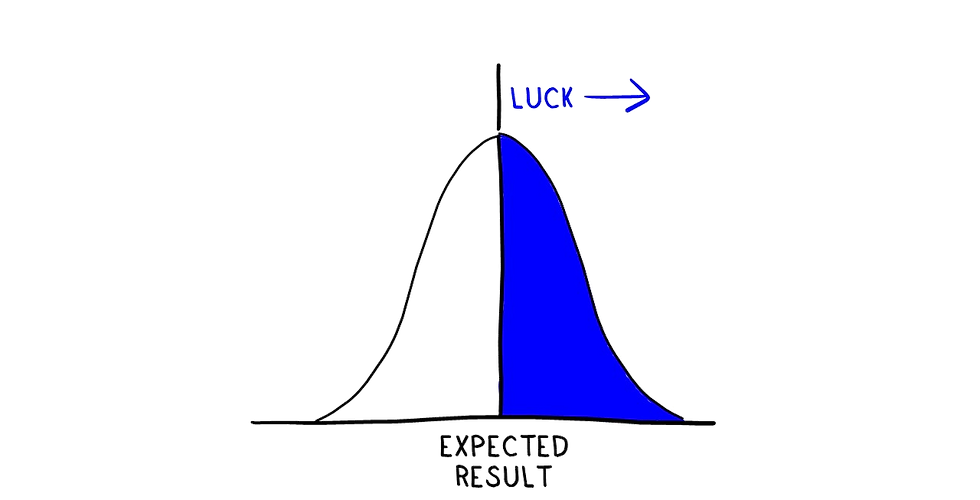

When we think about what might happen in the future, we tend to expect a particular result. You can think of this expected result as being the middle of the probability distribution.

Risk, then, is the chance that reality will not meet our expectation. Further, risk is the chance that our expectation will not be met in a way that is worse than what we expected.

Our expectations can be exceeded, as well. This would happen when we get better results than we were expecting. This you’ve probably heard of as luck.

Morgan Housel, author of The Psychology of Money, tells us that luck and risk are siblings. The idea is that we don’t control hundred percent of our outcomes with our actions. There is an outside force. When that outside force works in our favor, it’s luck. When that outside force works against us, it’s risk.

PROBABILITY OF RISK SHOWING UP

There are two dimensions of risk to consider. When we think about what could go wrong, the first question to ask ourselves is how likely it is that the risk will show up. The jargon here is thinking about the probability that something bad will happen. If something is more likely to happen and it is riskier than something that is less likely to happen.

For example, imagine standing on a cliff. If you are far away from the edge, then it is pretty unlikely that you will fall off the edge. Therefore, walking far away from the ledge is less risky.

On the other hand, if you stand right next to the edge of the cliff, it is far more likely that you will fall. Therefore, walking close to the edge is more risky.

The probability says nothing about what will actually happen if you fall. It only considers the chance that you do fall.

Thus, we also need to consider the consequences.

CONSEQUENCES IF RISK SHOWS UP

The second dimension of risk is what happens to us if the risk shows up. This is about the consequences. If you assume the risk shows up (no matter what the probability is), what would happen? This is a question that many people avoid. Sometimes the worst-case scenario isn’t as bad as we think (mostly, this is because we are ingrained with a negativity bias). Other times it’s far worse than we ever considered because we never stop to think about what would happen.

Using the cliff example again, if we assume that we're going to fall but it’s only 6 inches high, then the consequence of us falling are quite low. To say that another way, something with tolerable consequences, regardless of the probability, is less risky.

However, if following off the cliff leads to a 100-foot drop to rocky ground, those consequences are quite dangerous. Something with dangerous consequences, no matter how likely it is, is considered more risky.

Magician Penn Jillette once said that walking a tightrope is the same trick if it's three feet off the ground or 100 feet in the air. The reason an audience wouldn’t care about a lower tightrope is that there are no consequences. Audiences like risk.

Another example might be helpful. I’m driving my car down a winding road, then there is a risk that I will move out of my lane at some point. The probability of me leaving my lane will depend on many factors, such as whether it’s night or day, foggy, or if there's snow on the ground. But regardless of how likely it is, if I leave my lane, it’s probably no big deal. I can just get back into my lane. If, however, there are concrete barriers that are used as lane dividers on the same road, then even though the likelihood stays the same, the consequences are higher. Because the risk is higher, I’m more likely to drive slower.

TYPES OF RISK

Both dimensions of risk should be considered, and we can even chart this in one grid. We can plot how likely it is on the horizontal axis and the consequences on the vertical axis.

The upper right quadrant is things that are likely to happen and have dangerous consequences. The street name for this quadrant is “being dumb.” This would be something like jumping off a building just to see what it’s like. You know the risk is going to happen, and it’s going to be bad.

The upper left quadrant is things that have disastrous consequences but are unlikely to happen. This is a scary quadrant because, even though it’s probably not going to happen, it could. And if it does, that would be devastating. This would be like my house burning down, destroying somebody’s property with my car, or requiring expensive medical procedures.

The lower left quadrant is where things are unlikely to happen, but if they do, you can handle it. This is like getting a flat tire on your way to the store. It doesn’t happen very often, but you can easily change a tire or call for assistance.

The lower right quadrant is where the bad thing is probably going to happen, but the consequences are very tolerable. This can be something like your power going out at home. This could be somebody merging in front of you when they knew their lane was ending. Or it could be stumbling over your words while giving a presentation at work.

When we think about risk in terms of these four quadrants, we can think about each quadrant differently. The upper right quadrant, where it’s very likely that the event will happen and will be dangerous, we just stay away from that quadrant. We don’t participate.

In the upper left quadrant, we can shelter ourselves from these unlikely, catastrophic events with insurance policies. It is important to note that insurance only covers financial risk. It does not cover emotional and psychological risks that would come along with those same events.

The lower left quadrant is things that don’t happen very often, but if they do, it’s not that bad. This is just a minor hiccup in an otherwise good day.

Finally, the lower right quadrant, which consists of things that are going to happen but aren’t really that bad, should be baked into our expectations. Changing our expectations changes how we experience these events. For example, if I expect the power to never go out, I might be very irritated when it goes out. If I expect nobody to ever emerge in front of me, then I will be irked when somebody eventually does. If I expect to never flub my words at work, I will always be embarrassed with myself. Changing our expectations lessens the impact of these events.

REAL RISK

The long-running soap opera Days of Our Lives uses the slogan, “Like sands through the hourglass, so are the days of our lives.” My interpretation of this is that time keeps moving forward the same way sand passes through an hourglass.

Thus, I like to think of our lives as being kind of like an hourglass. But instead of it being an hourglass, I like to call it a lifeglass.

In the same way sand moves continuously through an hourglass from the top chamber to the bottom chamber, the moments we live pass through the present moment. The present moment converts all remaining life into the life that we lived.

Unfortunately, unlike an hourglass, we don't get to see the top chamber. The top chamber is covered up by what I call the Uncertainty Curtain.

This means that the past, or the bottom chamber representing the life we've lived, can't be changed nor experienced. It also means that the bottom chamber represents our memories and lessons learned. It represents the story we tell ourselves about our lives and our role in the world.

It also means that all we can experience is the present moment, where the top chamber empties into the lower chamber.

But the Uncertainty Curtain keeps us from knowing how many moments we have left. We have right now, and that's all we know. Eventually, our top chamber will be empty, and our lives will come to an end. It's in these moments that author Bronnie Ware reminds us that there are common regrets people have when they come face-to-face with the fact that the top chamber is nearly out.

Real risk, then, is not making the best use of our lives. It's wasting our life. Take this moment to connect with your personal values and sources of meaning. Design your life in such a way that you can look back on your life with pride and say that you do it again if you had the chance.

A meaningful life exists at the intersection of our personal values, purpose, and narratives. There are small risks that we all face, and we can learn to manage those risks. But there are bigger risks that should not be ignored.

You get one life; live intentionally.

Subscribe to Meaningful Money

Thanks for reading. If you found value in this article, consider subscribing. Each week I send out a new post with personal stories and simple drawings. It's free, and there's no spam.

If you know someone else who would benefit from reading this, please share it with them. Spread the word, if you think there's a word to spread.

REFERENCES AND INFLUENCES

Ariely, Dan & Jeff Kreisler: Dollars and Sense Bloom, Paul: The Sweet Spot Boniwell, Ilona: Positive Psychology in a Nutshell Clements, Jonathan: How to Think About Money Ellis, Charles: Winning the Loser’s Game Emmons, Robert: THANKS! Hagen, Derek: Your Money, Your Values, and Your Life Hefferon, Kate & Ilona Boniwell: Positive Psychology Housel, Morgan: The Psychology of Money Irvine, William: A Slap in the Face Ivtzan, Itai, Tim Lomas, Kate Hefferon & Piers Worth: Second Wave Positive Psychology Kahneman: Daniel: Thinking Fast and Slow Kinder, George & Susan Galvan: Lighting the Torch Kinder, George & Mary Rowland: Life Planning for You Krueger, David: A New Money Story Krueger, David & John David Mann: The Secret Language of Money Newcomb, Sarah: Loaded PositivePsychology.com: Realizing Resilience Masterclass Reivich, Karen & Andrew Shatte: The Resilience Factor Robin, Vicki: Your Money or Your Life Wagner, Richard: Financial Planning 3.0 Wallace, David Foster: This is Water Ware, Bronnie: The Top Five Regrets of the Dying Yalom, Irvin: Staring at the Sun Zweig, Jason: Your Money and Your Brain

Comments